First Encounter

For most fans of action cinema, kung fu superstar Jackie Chan first appeared on the scene in the Hollywood hit, ‘Rush Hour’ (1998). In Asia, Chan had already been firmly established as the ‘new king of kung fu’ for 20 years.

Initially, Jackie’s greatest challenge, in terms of the Western market, was to convince audiences that he was in no way ‘the new Bruce Lee’. Lee remains the benchmark for Chinese action heroes and, indeed, the only kung fu movie icon that most regular folk can name.

An earlier attempt to launch Jackie Chan internationally, ‘Battlecreek Brawl’ (1980), was billed as being ‘from the director (Robert Clouse) and producer (Fred Weintraub) of Bruce Lee’s ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973)’. However, the film itself owes much more to the kung fu comedies with which Chan had made his name in the east.

It took a while for Jackie to develop a broad worldwide fan base. As late as the 1980s, British film critic Iain Johnstone was still describing Chan as “a cult waiting to be cultivated”. Around the same time, I pitched a BBC arts programme on their interviewing the then little-known martial arts movie star Donnie Yen. I told them he was “the new Jackie Chan.” “Who is Jackie Chan?”, they asked. I had to fall back on the old “he’s the new Bruce Lee” ploy; to be fair, Donnie was certainly nearer to being a new Lee than a new Chan.

Ten years earlier, I’d moved to London, temporarily, to enroll at a school for radio DJs. The only lasting benefit I enjoyed from this experience was the fact that I got to see so many second run Hong Kong kung fu movies in the capital’s Chinatown, just down the road from the National Broadcasting School on Greek Street. In a seedy theatre below Wardour Street’s Hong Kong Cultural Centre, I played truant to watch a whole series of the wave Chinese actioners, including Jackie Chan’s breakthrough films, ‘Snake in The Eagle’s Shadow’ (1978) and ‘Drunken Master’ (1978). This was in the pre-video era. Short of dragging someone to that same theatre, there was no way to spread the word. For most film fans, kung fu cinema died with Bruce Lee. It was only after the advent of VHS tapes that I could only introduce my friends to Lee’s clown dragon successor.

It was on videotape that I watched Jackie’s various earlier movies, the films he had before his breakthrough double bill. In terms of lead roles, Chan had starred in ten films, of wildly varying quality, for director/producer Lo Wei. Jackie Chan has also been a co-lead in director John Woo’s ‘Hand Of Death’ (1976) and had walk on roles in a number of early Golden Harvest action movies. This last category included ‘Hapkido’ (1972).

It was in that context (‘Spot the Jackie cameo!’) that I cajoled London’s pirate king of Hong Kong cinema, Rick Baker, into giving me a copy of ‘Hapkido’ (1972). This wasn’t Rick Baker the Hollywood special effects wizard. This was Rick Baker the special effect.

Rick Baker was a key figure in the development of the UK as a market for Hong Kong action cinema. In Rick’s mind, I think he was supposed to become some major multi-media Asian action guru. The reality was that he remained, at heart, an affable, bearded fellow selling bootleg tapes in Camden Market. In this regard, he performed an invaluable service, to me and many others.

The kung fu films I wanted to see were simply not legally available anywhere else in the UK. I could not have become an expert on the genre, nor written my ‘Hong Kong Action Cinema’ book, or indeed this one, without the help of Rick Baker. Just as I was finishing this chapter, Rick made a rare visit to Hong Kong, and came to visit my hidden kung fu fortress in Kwai Fong. It was great to see him and to reminisce about the good old, bad old days of the UK’s Hong Kong film fan community.

The version of ‘Hapkido’ (1972) Rick gave me back in those days was blurry, letter-boxed and in Mandarin. It was still a revelation. I realized that, even during Bruce Lee’s lifetime, the Golden Harvest studio had presented the world with a completely different action aesthetic. And one with, arguably, an even greater long-term impact on the genre than Lee’s had. The Little Dragon’s screen fighting style depended on him being around to execute it; with ‘Hapkido’ (1972), Sammo Hung detailed a new way to depict martial arts on screen, one that established a ‘house style’ for future Golden Harvest kung fu films.

Years later I picked up a second hand video copy of ‘Hapkido’ (1972) in Melbourne, Australia. This tape features one of the most unintentionally hilarious English dub tracks ever provided for a Hong Kong action movie.

The whole film had originally been dubbed with the relevant characters referring to the art practiced by the Chinese heroes as ‘kung fu’. It was only later that someone pointed out that the main fighting style on display, and, in fact, the title of the film, was ‘Hapkido’. Rather than go to the expense of redubbing the whole film, a pair of voice-over artistes, one male, one female, went through the film replacing the words “kung fu” with the term “Hapkido”. The distributors decided, with some justification that, so long as the action was up to standard, no-one would care. The result has to be heard to be believed, and, to this day, I can’t take the word ‘Hapkido’ seriously.

Back Story

There’s a misconception that Sammo Hung, Jackie Chan and the rest of their generation came into the business on the basis of their ‘kung fu’ skills. In fact, few of them had experience of actual kung fu training or spent significant time training under a kung fu sifu/teacher, in a mo kwoon, a traditional Chinese martial arts school.

What they did have was an innate physicality, from their long years of study at Yu Jim-yuen’s Chinese Opera academy. This ancient performance art has various regional versions. Jackie Chan and his cohorts studied primarily the Beijing Opera. It shares the same name as its European counterpart, and some common characteristics. Both Chinese and western Opera feature extravagant costumes and sets, and a unique form of vocal performance adored by its devotees. The Beijing Opera includes dazzling displays of acrobatics, with bodies and weapons defying gravity, live on stage. With the exception of Sammo Hung, Chinese Opera performers are much lither than their Italian counterparts. To see a European theatrical form that resembles the Chinese Opera, watch the Darmora Ballet performance in the film ‘Gaslight’ (1940). Jackie Chan and his fellow Opera-trained players brought their energetic grace to their on-screen interpretation of whatever was the popular fighting style du jour.

In the Bruce Lee era, the fighting movements seen in Hong Kong actioners tended to be generic kicks and punches. Lee himself rarely displayed any specific ‘kung fu’ moves in his movie fights. While he was making his films at Golden Harvest, Bruce Lee actually did more to promote the Korean martial arts than he did the Chinese ones. Bruce talked Raymond Chow into signing his friend, the Washington-based Taekwondo master Jhoon Rhee, to star in ‘When Taekwondo Strikes’ (1973). He hired hapkido exponent Whang In-shik to play a Japanese heavy in his directorial debut, ‘The Way Of The Dragon’ (1971). Whang In-shik’s instructor, Chi Hon-tsoi, appeared in Lee’s unfinished ‘Game Of Death’ project. Lee’s American opponents Chuck Norris (‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972)) and Bob Wall (‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972) and ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973)) were both exponents of tang soo do, yet another Korean martial art.

While ‘Hapkido’ (1972) would put the art on the Hong Kong cinema map, the style was already having a disproportionate influence on American action movies. In the surprise hit indie ‘Billy Jack’ (1971), the late hapkido master Bong Soo Han trained lead actor Tom Laughlin and doubled for him. Bong got to go into action himself when he played a character in the sequel, ‘The Trial of Billy Jack’ (1974). The same year ‘Billy Jack’ (1971) came out, Sean Connery’s James Bond had to fight two lady hapkido-ists, Bambi (Lola Larson) and Thumper (Trina Parks) in the 007 flick ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ (1971). Years later, the aforementioned Bong Soo Han would choreograph a fight for Connery in ‘The Presidio’ (1988).

[redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

The star of the film is ‘The Angry River’ leading lady Angela Mao Ying, then being billed as Golden Harvest’s ‘Queen of Kung Fu’. Her father, Mao Yung-kang, had run a professional ballet troupe in the east coast province of Chekiang. After the Communist takeover in 1949, Mao and his wife fled across the neighboring Straits to Taiwan. Angela, whose real name is Mao Jing-jing, was born there in 1950.

At the age of 6, Mao was apprenticed to a Chinese Opera sifu/teacher at the Fu Hsing Dramatic Arts Academy, an experience which mirrored that of her later mentor, Sammo Hung. Though Sammo also served as a movie-making ‘sifu’ to Mao, he is actually two years younger than her junior.

At the age of 12, Angela embarked on a 24 city American tour with an Opera performance troupe. She also performed in Thailand and The Philippines. On a trip to Japan, she performed in Tokyo’s Imperial Theatre. As was traditional, Mao performed under a stage name, ‘Fu Jing’. The ‘Fu’ was taken from the ‘Fu Hsing’ school, the ‘Jing’ from her birth name, Mao Jing-jing. In Hong Kong, Master Yu Jim-yuen observed the same tradition, giving Sammo, Jackie Chan and his other students stage names beginning with ‘Yuen’.

The Fu Hsing school also produced B-list swordplay star Chang Yi (‘Bandits from Shantung’ (1972)) and Golden Harvest regular James Tien. Angela Mao would star with both her former classmates in the swordplay epic ‘Thunderbolt’ (1973). This was the first Golden Harvest film shot at their new Hammerhill Road studios.

Prior to being signed by Golden Harvest, Mao had auditioned for ‘Dragon Inn’ (1967), an arthouse swordplay film from former Shaw Bros director King Hu. The director, who had earlier made Cheng Pei Pei a swordplay star with his ‘Come Drink With Me’ (1966), was duly impressed by Angela Mao, though he didn’t sign her at that time. King Hu and Mao Ying would later work together, after Mao was signed to Golden Harvest, on the director’s masterful ‘The Fate of Lee Khan’ (1973). When Golden Harvest was first formed, the company was keen to find a female star to rival the popularity of the Shaw Brothers’ swordplay heroines, and in particular Cheng Pei Pei.

Raymond Chow, who had worked with Cheng Pei Pei when he was at Shaw Bros, brought the actress herself back to Hong Kong from the US. Cheng made two films for Golden Harvest, ‘None but the Brave’ (1973) and ‘Whiplash’ (1974), neither of them provided the expected comeback hit for the actress.

Angela Mao was 20 years old when, in the summer of 1970, she signed with Golden Harvest. She had already made her film debut in an obscure Taiwanese actioner, ‘The Eight Bandits’ (1968), but this was Mao’s real shot at the big leagues.

Angela Mao’s first two films for the studio, ‘The Angry River’ (1970) and ‘The Invincible Eight’ (1971) showed her applying the kind of stylized weapons skills she’d learned at the Chinese Opera. It was only when she shot scenes for ‘Lady Whirlwind’ (1972) that she started to develop a style of her own. The film was shot on location in Korea, and, at choreographer Sammo HungungHun’s urging, Mao commenced her intensive hapkido training.

The male lead of ‘Hapkido’ (1972), Carter Wong, was making his screen debut. Carter was introduced to Huang Feng by a friend from the Royal Hong Kong Police Force. Huang mentioned that Golden Harvest was looking for new martial arts stars, and the friend mentioned that the police had a karate instructor who might fit the bill. Reasoning that anyone old enough to teach karate to seasoned cops must be at least middle-aged, Huang suggested that this sensei/instructor might be too old to start a film career. He was surprised to learn that the man concerned was a youthful expert in Goju Kai karate, though the original trailer for ‘Hapkido’ (1972) imaginatively describes him as a ‘Ninjitsu master.’ Carter Wong was duly signed by Golden Harvest as a new action actor.

[redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

Synopsis

Three Chinese youngsters, trained in the Korean martial art hapkido, return to 1930s China to open their own school. When the head of a rival Japanese karate academy pushes them too far, our heroes must risk their lives to uphold the honor of their country and their style.

Blow-by-blow

The film opens with the original Golden Harvest logo, a red ‘GH’ superimposed on a field of waving wheat, and, against the same background, a card trumpeting the fact that the film is in ‘Dyaliscope’, whatever that was, and Eastmancolor.

The first scene, supposedly set in the countryside outside 1934 Seoul, was actually shot in the New Territories of Hong Kong, with Chinese actors in Korean national dress. At the time in which the film is set, Korea was suffering under the Japanese occupation. In this scene, the invaders are represented by a shifty little official. He is played by Ma Lo, who was also the film’s production manager. Ma Lo had previously played the Japanese dojo secretary that Bruce Lee declines to beat up in ‘Fist of Fury’ (1972).

Our three leads, Yu Ying (Angela Mao Ying), Ta Chin (Carter Wong) and Fan Wei (Sammo Hung), are enjoying a picnic when they are accosted by Ma Lo’s character and his three henchmen. At the end of the brief fight that follows, Ma Lo picks up a metal plaque that Hung has dropped. It has the Chinese characters for ‘Hapkido’ engraved upon it.

We cut to an innovative mixed media title sequence, created by Chin Ying-sai. It was a joy to finally see this on a wide-screen DVD release, as the pan-and-scan on my old video copy lost half the image. The forecourt and interior of the Korean Hapkido academy were built inside a Golden Harvest soundstage. Our three Chinese heroes take part in a graduation exercise. Painted images of the leading players and written bi-literate credits are superimposed in an attempt at a Pop Art style. Sammo Hung gets two credits, one under his ‘acting’ name, ‘Hung Chin-pao’, and another as action choreographer ‘Chu Yuan-lung’.

‘Yuan Lung’ had been Sammo’s stage name at the Chinese Opera School where he had studied alongside Jackie Chan and Yuen Biao. As mentioned above, all the Opera school students had been given names featuring the character ‘Yuen’, as a sign of respect for their teacher, Yu Jim-yuen. Some, like Yuen Biao, have kept that name to this day. Sammo used his when he began his career as a choreographer, but has since used his given name in all his different guises.

Both Ta Chin and Fan Wei fail to pass the invincible senior student, played by Whang In-shik. Despite his being the most physically impressive Hapkidoist in a film called ‘Hapkido’ (1972), Whang’s character is never given a name. The credits end with Whang In-shik’s character dispatching Wei, before Ying (Angela Mao) leaps into action. For this fight, Angela Mao is doubled for the more acrobatic moves.

This segues into an extended lecture and demonstration in which real-life grandmaster Chi Hon-tsoi expounds upon the nature of Hapkido. His school logo is an eagle with an arrow in its talons. Its featured on a metal plaque on one wall, and beneath it are the words ‘Dai Hon Dai Kwok Hapkido Fei Ying chung kwoon/Great Korean Empire Flying Eagle Hapkido central school’.

The physical skills displayed are awesome for any era, but especially for 1972. This sequence manages to convey the sheer range of hapkido techniques. Sammo Hung makes good use of slow-motion to capture every movement. Nobody puts the ‘art’ into the ‘martial’ the way Sammo does.

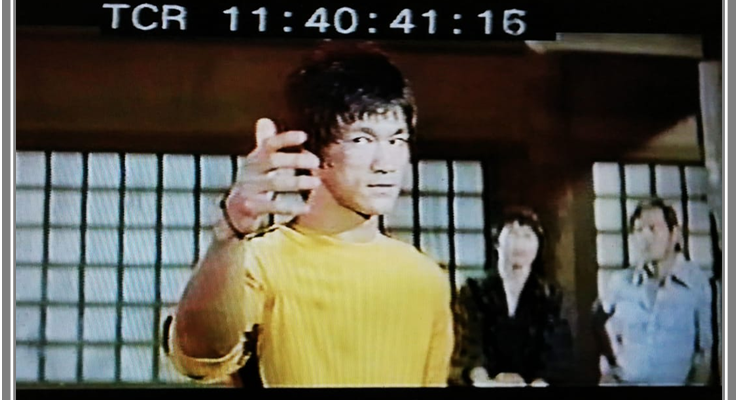

The young Jackie Chan can be glimpsed among the hapkido students. Later in the film Chan turns up again as a karateka at a Japanese dojo. It makes for a fun drinking game, something Jackie Chan himself knows all about. Take a shot every time you see Jackie in ‘Hapkido’(1972).

Somehow, the original negative of ‘Hapkido’ (1972) was damaged, and, for many early video releases, this sequence was curtailed. It was only after several years that a restored version was finally made available.

[redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

‘Tiger’, a burly student from the Shaolin kung fu school is played by Chin Ti. Chin Ti played the comic relief character in Bruce Lee’s directorial debut, ‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972). This was after, much to Lee’s anger, ‘The Big Boss’ (1971)/ ‘Fist of Fury’ (1972) veteran Lee Kwan, proved unavailable. ‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972) was being shot at the Golden Harvest studios at the same time as ‘Hapkido’ (1972), meaning that Chin Ti had to run back and forth between sets. Chin Ti later played a sleazy film producer in the outrageously camp Shaw Brothers produced Bruce Lee bio pic, ‘Bruce Lee and I’ (1976).

Tiger takes Wei to a local teahouse. As soon as the action moves to the studio interiors, we suddenly get bustling streets with extras visible in the background. There’s an obvious discrepancy between the location exteriors, shot in what was very obviously an abandoned Pat Heung village, and the fake ones at the studio, which indicate a thriving township. The waiter who serves Tiger and Wei is prolific bit-part player Tsang Choh-lam, He’s here taking a break from his usual roles of scheming gambler and/or opium addict. The teahouse owner, Lee Ho Yan, went on to play Bruce Lee’s family retainer in ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973).

A fight erupts after two members of the Japanese school refuse to pay their bill. The one with the moustache is played by Suen Lam. Suen was a character actor who specialized in playing devious weaselly types. Director King Hu gave Suen Lam a more prominent role in his first Golden Harvest film, ‘The Fate of Lee Khan’ (1973).

The other fellow is Leung Siu-lung, a taekwondo black belt with impressive kicking skills. At the time of ‘Hapkido’ (1972), Leung was laboring away as a supporting player in films like Golden Harvest’s ‘Lady Whirlwind’ (1972) and Shaw Bros’ ‘The Casino’ (1972). Immediately after Bruce Lee’s death, Leung Siu-lung hoped his time had come. He was to be seen demonstrating his skills for the Hong Kong press in a park near the Lee family home in Kowloon Tong. The actor was, indeed, discovered by Seasonal Films’ director/producer Ng See-yuen, and cast in a trio of chop socky potboilers: ‘Call Me Dragon’ (1974), ‘Little Godfather from Hong Kong’ (1974) and ‘Kidnap in Rome’ (1976). Leung Siu-lung even took on the stage name ‘Bruce’, in deference to his idol. The Korean director Cheng Chang-ho gave ‘Bruce’ Leung his best role for Golden Harvest as co-lead in his ‘Broken Oath’ (1977). Leung Siu-lung found his true niche on TV, playing the Bruce Lee character, Chen Jun, in ‘The Fist’ (1982), a series based on Lee’s ‘Fist of Fury’ (1972).

The girl that the two Japanese assault, Sau, is played by Nancy Sit. As an ingénue, Sit starred in a dozen black-and-white dramas, but enjoyed her greatest fame as a TV star in the TVB series ‘Jaan Cheng/Kindred Spirit’ (1995-1999). At the time she was cast in that show, Sit had been retired for several years, but, after a difficult divorce, decided to return to the small screen.

Tiger proves to be singularly inept as a fighter, considering that he represents the Shaolin school. Wei leaps into the fray. The initial exchange between him and Leung Siu-lung sees an early use of powah faan/power powder. This is actually fuller’s earth spread lightly onto someone’s clothing. It then flies off when contact is made, thereby enhancing the impact of a blow. This was the first time audiences really got to see the crisp hand-to-hand fighting style of the burly Sammo Hung.

It’s hardly surprising that, as they were filming on neighboring stages, Bruce Lee would take note of Sammo’s skill. Sammo Hung was originally cast in Lee’s ‘Game of Death’ (1972/78), but, much to Bruce’s annoyance, Sammo had to bow out due to a scheduling conflict. Hung was replaced by the burly Singaporean Chieh Yuan. Hung’s fellow ‘Hapkido’ (1972) actor, Carter Wong, remembers Lee offering him a different role in the ‘Game of Death’ (1972/78). Bruce Lee’s untimely passing meant that Wong never shot footage for it.

Carter Wong also came close to appearing in Bruce Lee’s breakthrough international film, ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973). Lee made detailed notes regarding a revised opening scene for the film, one that he shot after the American director of credit, Robert Clouse, had left Hong Kong. His original version depicted a Shaolin training camp, with Carter Wong as one of the kung fu fighters displaying their skills. In the end, Bruce Lee simplified his concept down to a one-on-one bout between himself and another ‘Hapkido’ (1972) star, Sammo Hung.

The beaten karate fighters report back to their seniors at the Black Bear dojo. The tone of this scene is similar to a similar ‘plotting revenge one in ‘Fist of Fury’ (1972). The two senior fighters are played by Lee Kar-ding and Pai Ying, and the conniving advisor, Zhang, by Wei Ping-ao. Wei Ping-ao is playing virtually the same role he had played in ‘Fist of Fury’ (1971), and was concurrently portraying in Bruce Lee’s ‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972). Wei Ping-ao was another Golden Harvest regular running back and forth between the two sets. Just as ‘Fist of Fury’ (1972) had cast real Japanese in the roles of senior karateka, the master of the Black Bear dojo, Toyoda, is played by another ‘Zatoichi’ (1962-1989) film series regular, actor Teruo Yamane.

Back at the Eagle dojo, the three hapkido experts divide their time between training their fighting moves and using their bone-setting skills to heal the local workers. Historically, most Chinese martial arts schools were primarily dit da, literally ‘falls and hits’ herbal treatment clinics.

Some Black Bear dojo heavies turn up to cause trouble, with one of them eyeing up Yu Ying and complaining that he has ‘itchy hair’. This is a crude reference to a Chinese slang term for male arousal. The burly guy who fights with Ta Chin is played by Robert Chan. Chan was a family friend of Bruce Lee, and played one of the waiters in Lee’s ‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972). For the stunt where Wong throws Robert Chan across the dojo, the latter is doubled by Jackie Chan, who for some reason is wearing a white sash, where Robert Chan is wearing a black one.

As Ta Chin (Carter Wong) goes to try to make amends at the Black Bear dojo, Pai Ying and his group of karateka are marching to the hapkido school. The streets are so deserted; it seems that no-one lives in this town apart from angry martial artists. Pai Ying breaks the hapkido dojang chu pai/signboard, the ultimate gesture of disrespect in the martial arts world.

The bullying karateka then accosts Ying (Angela Mao) telling her that, as Korea is occupied by Japan, the art of hapkido, too, belongs to the Japanese. He’s actually correct, albeit not politically so, in that the development of hapkido was undoubtedly very much influenced by the Japanese martial arts of jujitsu and karate. The Chinese characters used for ‘hapkido’ are the same as those used for the Japanese art of ‘aikido’.

Leung Siu-lung’s character and his fellow Japanese thugs go to harass the local Chinese in the marketplace. This is another well populated Golden Harvest studios interior. The guy walking directly behind Leung’s karateka is the late Lam Ching-yin. Lam is a martial arts stuntman later to find fame as an actor as the star of ‘Mr.Vampire’ (1985) and its sequels.

Fan Wei happens onto the scene, leading to a fight scene in which Sammo shows that he is already, even at this early stage, a true master of screen fight choreography. For some years, the Golden Harvest movie sales catalogue described Sammo as Bruce Lee’s student, in terms of action directing. ‘Hapkido’ (1972) was shot before Sammo worked with Lee. It’s evident that Sammo had learned from Lee’s work on ‘Fist of Fury’ (1971), but his fights have their own distinct rhythm. To see how far ahead Hong Kong film choreography was from its other technical aspects, just check out the set’s painted background ‘flats’ that represent the rest of the town.

Ta Chin’s meeting with Toyoda goes badly. As he leaves, Ta Chin (Carter Wong) is accosted by a group of hostile, sword-wielding Japanese. They are, right to left, Hsu Hsia, later to become an action director, Shaw Bros actors Chik Ngai-hung and Law Keung and finally actor/action director Chan Cheung. In the background we can see Tony Ching Siu-tung, later to become an award-winning choreographer and director. Following the impact made by the dojo fight in ‘Fist of Fury’ (1971), Golden Harvest decreed that ‘Hapkido’ (1972) should feature several such scenes, with this being the first.

Ta Chin must dispense with the katana wielding Hsu Hsia and Chan Chuen, before taking on a whole dojo full of karate students. Sammo Hung’s choreography gives Carter Wong the best single fight scene of his career. Our hero finally meets his match when he duels the school’s chief instructor, played by Taiwanese actor Pai Ying. The chief cripples the Chinese fighter’s right arm, but lets him live.

Sammo executes a slick cut between the limb snapping and Toyoda’s tabi/Japanese slipper clad feet separating. Comic actor/director Stephen Chiau took the same gag to suitably ridiculous lengths for a scene in his film ‘Forbidden City Cop’ (1996).

Though born in Sichuan, actor Pai Ying spent most of his life in Taiwan where, after finishing his national service, he enrolled as an apprentice actor with the Union Film Company. Pai Ying made his debut in King Hu’s classic ‘Dragon Gate Inn’ (1967), and went on to appear in the director’s ‘A Touch of Zen’ (1971). He started working on Hong Kong action films when he was cast by ‘Hapkido’ (1972) director Huang Feng in Golden Harvest’s first film, ‘The Angry River’ (1971).

Duelling Pai Ying seems to have become a rite of passage for Hong Kong martial arts actresses. A little over a decade later, he was cast as Michelle Yeoh’s nemesis in her second starring vehicle, ‘Royal Warriors’(1986). That film was made by D&B Films, a company jointly owned by Yeoh’s husband to be, Dickson Poon, and ‘Hapkido’ (1972) star Sammo Hung.

The maimed Ta Chin is dumped back at the hapkido school. It’s interesting to note the smooth dolly movements Huang and Director of Photography Lee Yau-tong achieve in this relatively inconsequential scene, especially when compared to the stiff, stagey handling of similar material in Lo Wei’s films.

Adding insult to injury, Toyoda sends his interpreter Zhang to demand that the hapkido dojang/school hand over Fan Wei and then close down. A class is in progress, with local Chinese workers learning hapkido. Sammo Hung’s grandma, Chin Tsi-ang, plays one of them. The four karateka accompanying Zhang include the young Jackie Chan, but he doesn’t get to fight. Its actor/action director Chin Tsi-ang who attacks one of the students (stuntman Yuen Wah) and then gets knocked down by Yu Ying (Angela Mao).

Aided by his new friend Tiger, Fan is forced to hide out in a disused warehouse. This is a well-crafted Golden Harvest studio set. Yu Ying goes to the Black Bear dojo to try and make peace. To ‘prove’ the inferiority of the Korean martial art, Toyoda fights his pet hapkido black belt. The man is played by martial arts actor Yang Wei. The burly Toyoda is doubled for a flying kick by Sammo himself. Outraged, Yu Ying uses the Korean ‘rod of correction’ given her by Chi Hon-tsoi to punish the treacherous hapkido-ist played by Yang Wei.

Yang Wei was a supporting actor in several Hong Kong actioners. Like Sammo Hung, he married one of the beautiful Korean women he met while shooting on location in that country. Yang got the biggest role of his career when the young director John Woo saw something interesting in his demeanour. Woo then cast him as one of the stars of his ‘Hand of Death’ (1976), alongside a young Jackie Chan. At the time ‘Hapkido’ (1972) was shot, Carter Wong was living in the dormitories behind the Golden Harvest studios, where he was later joined by the aforementioned John Woo. Wong went on to star in Woo’s directorial debut, ‘The Dragon Tamers’ (1975). This was shot on location in Korea with, among other ‘Hapkido’ (1972) alumni, Chi Hon-tsoi in the cast.

The fight between Yu Ying and Yeung Wai’s hapkido expert also sees Yu Ying uses one of the art’s more unconventional weapons, the umbrella. Despite her teacher’s constant demands that his students exercise yan/patience, Yu Ying finally kills her opponent. When the karate students line up to prevent her leaving the dojo, the one on the far left of the screen is, again, Jackie Chan. Toyoda decrees that Yu Ying be allowed to leave unchallenged. Her fighting skills have impressed him, and Toyoda plans to make use of them when he eventually takes over the hapkido school.

This was also a plot point in Lo Wei’s ‘New Fist of Fury’ (1976), where a bullying karate sensei played by martial arts star Chan Sing seeks to unite all the Taiwanese kung fu schools under the Japanese flag.

Tiger inadvertently reveals the location of Fan Wei’s hiding place to the Japanese, who then follow him to the warehouse. Director Huang Feng’s staging here is surprisingly clumsy. It seems that Fan Wei simply sits and watches as Pai Ying’s character beats Tiger to death.

The ensuing brawl between Hung and the various karateka takes in every inch of the elaborate warehouse. It’s another ground-breaking set piece, in terms of the way Hung keeps everything in motion, with a constant rhythm to the melee and props being smashed and crashed at every opportunity. It’s a blueprint for the kind of sequences seen in the later Jackie Chan films. As the action shifts to a first floor landing, Jackie, playing one of the Japanese fighters, gets a chance to shine as Sammo unleashes a slow motion jumping kick that sends Jackie Chan crashing through a breakaway barrier and down to the floor below.

Fan Wei finally meets his match in Pai Ying. This is quite a reach, as the actor is obviously no equal, physically, for Sammo Hung. At the end of the scene, Wei Ping-ao gets the best subtitle in the film: “Hapkido? I’d call the damn thing ‘crapkido’.” This despite the fact that, when he and Pai Ying go, they leave behind the (presumably) dead bodies of all the karate fighters they brought with them.

The shots where Yu Ying goes in search of Fan Wei are filmed day-for-night. They lead into an atmospheric interior scene where she discovers the bodies of Tiger and her classmate. Only the inn-keeper and three local kung fu masters dare to attend Fan Wei’s funeral. The rest having been frightened off by the Black Bear school. Cheung Hei was always a handy guy to have at funerals. He read Fok Yun-kap’s eulogy in ‘Fist of Fury’ (1972), and here gets to deliver the bad news again.

Zhang turns up with a fresh spin on the ‘deliver insulting signboard/smash the signboard’ riff. Toyoda has offered to allow the hapkido school to continue as a franchise of the Black Bear school. He has gone to the trouble of creating a sign that reads to this effect. And you have to give Toyoda credit. It must have taken some time and money to come up with that chu pai.

[redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

Yu Ying and Whang In-shik’s nameless hapkidoka go to the Black Bear dojo for the final showdown. There’s a deleted scene where Sau tells them Ta Chin has been attacked, and the two surviving hapkido experts find his body. This explains Yu Ying’s grey uniform and white waist and hair bands, signifying that she is in mourning.

The karate fighters include, on the far left of their line-up, Corey Yuen, who later became a choreographer and director of great renown. Whang In-shik goes into action for his version of the dojo clearing scene. His kicking skills still look awesome today, especially when you consider that Whang performed everything live, on camera, without the aid of wires of CGI. He looks way better than anyone else then on the scene, including Bruce Lee. Lee’s kicking techniques were, by comparison, quite basic. That didn’t matter because he was Bruce Lee, and nobody else was.

Yu Ying steps in to take on Pai Ying’s character,, who seems to be the only one in the film capable of giving our heroes a match. To defeat him, she has to use the ‘light body skill’ she demonstrated in the opening scenes, and also her ‘pigtail of fury’, enhanced by a couple of ball bearings in her braids. Pai Ying’s karateka ends up with Hammer horror style facial injuries before Angela Mao, doubled for the acrobatic moves by stuntman Yuen Biao, finishes him off with a flying neck lock. After their duel, Mao obligingly tips the body face down so poor Pai Ying doesn’t have to lie there throughout the ensuing fight scene.

At about the time any sane Japanese would be slipping out the back way, Toyoda steps into the fray. Even when doubled by Sammo Hung, the karate master is no match for the Korean’s furious fists and feet. Toyoda finally resorts to his Japanese katana/long sword. Whang In-shik’s character is forced to use anything at hand to protect himself from its blade. The hapkido master has sustained severe wounds when Yu Ying returns to the fray, managing to disarm Toyoda and throw him back and forward through the dojo’s shoji panels. She finally finishes him off with a kick to the neck.

Their revenge taken, the two hapkido experts leave, presumably to continue the fight against the Japanese back in Korea.

And then…

‘Hapkido’ (1972 had its premiere at Jordan’s Fai Lok Theatre in Hong Kong. It went into general release on the 12th of October, 1972, making it to the screen two months earlier than that year’s big money-spinner, Bruce Lee’s ‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972). It earned HK$870,000 at the local box office.

The field for action films was so crowded, and the local tastes so varied, that ‘Hapkido’(1972) didn’t even make it to that year’s list of Hong Kong’s top ten grossing films. Nevertheless, it further established Angela Mao Ying’s position as Golden Harvest’s action movie queen. It remains the actress’ favourite of her own films.Though the story focuses on a Korean martial art, ‘Hapkido’ (1972) was released in the US, misleadingly enough, as ‘Lady Kung Fu’.

Lawrence Van Gelder, reviewing the film under that title for The New York Times, observed that “aficionados of the recent wave of martial-arts movies can take comfort in the knowledge that the latest arrival…displays adequate reverence for the form they first knew and loved.” In perhaps the first review of a kung fu movie to cite Churchill, Van Gelder notes “the ultimate visitation on the principal villains of what (Winston) liked to call condign punishment’. (I had to look it up, too; it means ‘retribution appropriate to the crime or wrongdoing; fitting and deserved.’). He went on to observe that the music and effects soundtrack served the film better than the dubbed dialogue one did.

The above review came out during a period, May 1973, when there were two other ‘kung fu movies’ in the US theatrical Top Ten alongside ‘Hapkido/Lady Kung Fu’ (1972). These were Bruce Lee’s ‘The Big Boss’ (1971), released in the US as ‘Fists of Fury’, and ‘King Boxer’ (1972), released as ‘Five Fingers of Death’. The same year, American audiences would get to appreciate the talents of Bruce Lee and Angela Mao in the same film, the Warner Bros production ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973). They play brother and sister, but have no scenes together. Lee’s character avenges her suicide.

‘Hapkido’ (1972) wasn’t released in Japan until 1974. Not every Hong Kong action movie worked well in that market, but Japanese audiences had responded to Mao’s extended cameo in ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973). They liked the way her character chooses death before dishonor, samurai style. Mao flew to Tokyo to promote the film, performing a demonstration of her hapkido skills before a screening of the movie.

Angela Mao was called on to deliver a similar display in Sydney, Australia, when the film opened there. Her exchange of martial arts moves with veteran Aussie stuntman Grant Page was immortalized in ‘Kung Fu Killers’(1974). This was a documentary directed by the indefatigable Brian Trenchard-Smith, who later helmed the Jimmy Wang Yu vehicle ‘The Man from Hong Kong’ (1975). In 1974, Page and Trenchard-Smith flew to Hong Kong where they shot behind-the-scenes footage of former James Bond George Lazenby and Angela Mao on the set of ‘Stoner’ (1974). This was a project that Mao inherited from Bruce Lee. Lee had signed Lazenby to a three film deal, with the first of them to be ‘The Shrine of Ultimate Bliss’. After Lee’s passing, Angela Mao took over the Bruce Lee role of Chinese cop and was partnered with the George Lazenby for ‘Stoner’ (1974). And that’s quite a title for a film about a narc…

In terms of her Golden Harvest output, Angela Mao went on to shoot her best action scenes for choreographer Sammo Hung, in ‘The Tournament’ (1974) and ‘The Himalayan’ (1976), both of which were directed by her mentor Huang Feng. She also did sterling work for choreographer Yuen Woo-ping in director Cheng Chang-ho’s ‘Broken Oath’ (1977). After her contract with Golden Harvest ended, Angela Mao made some independent features, primarily in her native Taiwan. ‘Hapkido’ (1972) veterans Angela Mao, Carter Wong and Huang Feng were reunited on a Taiwanese project. This was after all their contracts with Golden Harvest had expired. Many of the actors Huang Feng had worked with, including Chan Sing from ‘Shaolin Plot’ (1977), gathered to shoot a ‘benefit film’ for him. This was ‘The Legendary Strike’ (1978), based on a typically convoluted tale from author Ku Lung. It turned out to be Huang Feng’s final film. Angela Mao later retired from the industry and relocated to New York. She currently operates a restaurant in the New York borough of Queens.

Her ‘Hapkido’(1972) co-star Carter Wong got his finest chance to shine in ‘The Skyhawk’ (1974), in which he was again choreographed by Sammo Hung. Carter Wong never really came into his own as a leading man in Hong Kong, and enjoyed his greatest success with a Taiwanese production, ‘The 18 Bronzemen’ (1976).

In terms of her Golden Harvest output, Angela Mao went on to shoot her best action scenes for choreographer Sammo Hung, in ‘The Tournament’ (1974) and ‘The Himalayan’ (1976), both of which were directed by her mentor Huang Feng.

In the 80s, Carter Wong relocated, temporarily, to the US. I met him for the first time in New York, where I attended the opening ceremony for his Yan Jeh Pai kwoon (literally ‘Patient Man School’). His well-appointed academy, the name of which employs a Chinese character (yan/patience) used prominently in ‘Hapkido’ (1972). It was situated in Chinatown, and the launch party drew many famous names from New York’s martial arts community. Carter Wong’s venture was being financed by a rather odd mother and son team, and it was hard to imagine how much an ambitious venture could stay afloat, financially, given the typical Manhattan rents.

Wong still had acting ambitions, though, and, when I met him, was in contention for a role in Michael Cimino’s ‘Year of the Dragon’ (1985). He later moved to Los Angeles, where John Carpenter used him to good effect as ‘Thunder’ in his homage to Hong Kong martial arts epics, ‘Big Trouble in Little China’ (1986). Today, if you want to describe to anyone who Carter Wong is, you just say “the guy who blows up and the end of ‘Big Trouble in Little China’ (1986).” They’ll know who he is.

Carter Wong was also hired, briefly, to train Sylvester Stallone for ‘Rambo III’ (1988) and then cast by B movie maestro Tony Zarindast in the low-budget thriller ‘Hardcase and Fist’ (1989). Carter Wong subsequently returned to Hong Kong, where he has focused his recent energies on promoting kickboxing tournaments.

After an auspicious debut in ‘Hapkido’ (1972), grandmaster Chi Hon-tsoi went on to work with Bruce Lee. He had a cameo in ‘Fist of the Unicorn’ (1973), a lackluster starring vehicle for Lee’s lifelong friend Unicorn Chan. Chi Hon-tsoi later shot scenes for Bruce Lee’s unfinished ‘Game of Death’ (1972) project. The premise of ‘Game of Death’ saw masters of various fighting arts guard the different levels of a multi-storey pagoda. Lee’s character and four comrades have to fight their way up the floors of the pagoda, with Lee providing an object lesson in the superiority of his Jeet Kune Do, which was more of a martial arts philosophy than a specific style.

Bruce Lee was very demanding, as is evident from extensive outtake footage showing Lee insist that Chi Hon-tsoi perform take after take during their fight sequence. Perhaps the experience soured the movie-making passion of the hapkido master. He was to make just one more cinematic appearance, in an early John Woo film, ‘The Dragon Tamers’ (1975), in which he duels his ‘Hapkido’ (1972) student Carter Wong.

[redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

Words to live by

At the funeral for Fan Wei (Sammo Hung), the venerable Cheung Hei observes that ‘Sun mong tsee hon/chun wang tse hon/the teeth won’t survive without intact lips’; meaning we all need to work together to devour this meal called life.

Final blow

‘Hapkido’ (1972) was, in its own way, easily as influential on Hong Kong action cinema as the Bruce Lee movies, and established a new style of martial arts.

| There are no products |